|

|

Esus

AKA: Essus, Esos, Hesus, Tarvos Trigaraunos.

While seemingly an important God in Gaul, there's little about Him on the

'Net. When I went looking for descriptions of Him, I found very, very

little. Because of this, I've decided to grab as much information as I

could, and fill a page about Esus.

This particular page will not only include what we know (concretely) about

Esus, but also what I have managed to gather via worship. Because I don't

want to muddle what we "know" and what I'm "guessing", I'll

be certain to cite my sources, and even block off the "scholarly" work

from my "conjectures". Section 1 will be about the scholarly

aspects, section 2 will be my inferences from that scholarly knowledge, and

section 3 will include my conjectures.

In all, please enjoy. If you have found something more worthwhile than

what I have, please tell me. I want

to know!

**Note 07/19/05: It has come to my attention that some people

are using this webpage to prove that Esus is, in fact, Jesus, or vice versa.

It is my stated conclusion that there is no evidence whatsoever that Esus and

Jesus are related. There is no evidence that this is the case, and the names

themselves cannot be derived from one another. Esus is derived from an Indo-European language, and Jesus is

derived from a Semitic language,

and they don't even mean similar things. To state that they are similar is not

only incorrect, it is uninformed. It's like saying that "can't" and

"cant" are related words because they look similar.

If someone feels really strongly about it, I'll be happy to exchange email

with you and chat civilly about it, but my site is not "proof" of this

idea. I do not support it. Esus is not Jesus. Jesus is not Esus. Period.

**Note 02/08/06: I've received a number of inquiries, so I

wanted to point to a full layout of my position in this "Esus=Jesus"

argument: Esus is not Jesus.

On with the scholarly aspects of Esus!

We'll start with the first of two literary primary sources on file for this God: the Roman

poet Lucian!

Lucian is our first source about Esus. He isn't noted as a great God to

worship, but as this is one of two literary sources, we have to run with it:

"...and those Gauls who propitiate with human sacrifices the merciless

gods Teutas, Esus and Taranis - at whose alters the visitany shudders because

they are as awe-inspiring as those of the Scythian Diana."

Lucan, Pharsalia I, 422-465 (http://www.kernunnos.com/deities/Taranis.shtml)

Here's another translation, with different line numbers:

Ligurian tribes, now shorn, in ancient days

First of the long-haired nations, on whose necks

Once flowed the auburn locks in pride supreme;

And those who pacify with blood accursed

Savage Teutates, Hesus' horrid shrines,

500 And Taranis' altars cruel as were those

Loved by Diana (18), goddess of the north;

All these now rest in peace. And you, ye Bards,

Whose martial lays send down to distant times

The fame of valorous deeds in battle done,

Pour forth in safety more abundant song.

While you, ye Druids (19), when the war was done,

To mysteries strange and hateful rites returned:

To you alone 'tis given the gods and stars

To know or not to know; secluded groves

510 Your dwelling-place, and forests far remote.

- Lucan, Pharsalia I, 495-510 (http://sunsite.berkeley.edu/OMACL/Pharsalia/book1.html)

(18) This Diana was worshipped by the Tauri, a people who dwelt

in the Crimea; and, according to legend, was propitiated by

human sacrifices. Orestes on his return from his expiatory

wanderings brought her image to Greece, and the Greeks

identified her with their Artemis. (Compare Book VI., 93.)

(19) The horror of the Druidical groves is again alluded to in

Book III., lines 462-489. Dean Merivale remarks (chapter

li.) on this passage, that in the despair of another life

which pervaded Paganism at the time, the Roman was

exasperated at the Druids' assertion of the transmigration

of souls. But the passage seems also to betray a lingering

suspicion that the doctrine may in some shape be true,

however horrible were the rites and sacrifices. The reality

of a future life was a part of Lucan's belief, as a state of

reward for heroes. (See the passage at the beginning of Book

IX.; and also Book VI., line 933). But all was vague and

uncertain, and he appears to have viewed the Druidical

transmigration rather with doubt and unbelief, as a possible

form of future or recurring life, than with scorn as an

absurdity.

This particular version

also includes the caveat: "It should be noted

that, as history, Lucan's work is far from being scrupulously accurate,

frequently ignoring historical fact for the benefit of drama and rhetoric. For

this reason, it should not be read as a reliable account of the Roman Civil War."

Recently, I stumbled across a citation in the L'année

épigraphique, 1985. This inscription was found, of all places, in Cherchell,

Algeria. The source is in French, and to the right, you will see the photo for

the inscription:

934) P. 123, n° 154; photo, fig. 9. Fragment de stèle de marbre blanc, brisée de tous côtés, sauf à g. : 28 × 20 × 5,5 cm. Le fronton triangulaire

était orné de trois rosaces et soutenu par deux colonnes. Ch. ép. sur le bandeau supérieur : 4 × 12 cm. Provient de la nécropole occidentale.

Peregrinus [---] | quod Esus fuit iuben[s---].

Peregrinus est un nom très courant. Plus surprenante est l'intervention du dieu gaulois Esus.

Correct citation of the above would read as follows:

AE 1985, 00934

Province: Mauretania Caesariensis

Location: Cherchell / Caesarea

The original publication of this inscription was in Ph. Leveau, Nouvelles inscriptions de

Cherchel, BAA, t. VII, 1, 1977-1979, p. 111-192, where it read

like this:

n° 154

Stèle de marbre blanc brisée en haut, à droite et en bas. L : 20 cm ; H : 28 cm ; ép. : 5,5 cm. Fronton triangulaire décoré de rosaces et soutenu par un cadre de colonnes. Champ épigraphique : H : 4 cm. H l. : 1,8 cm. Points séparatifs simples. Ligne 2, ligature VS. Nécropole occidentale.

PEREGRINVS[---

QVODESVS*FVIT*IVBEN[---

Ligne 2 : Esus est le nom d'un dieu gaulois, qu'il est étonnant de trouver ici.

The note "Ligne 2, ligature VS" explains why the word

"Esus" doesn't seem to actually appear after "quod." The V

and the S come together as a ligature, looking more like this: E∫\∫

(special thanks to Mary Jones for spotting this and explaining the process).

Something really interesting to note is that, despite a lack of iconography

associated with this particular inscription, we do appear to have a sand dollar

above it (it's been pointed out to me that this is probably not the case, however, given that sand dollars have 5 slits in them). Unfortunately, the rest of the inscription and monument is missing,

so whatever was on it is now lost.

While digging up the original photo for this artifact, I found something else

interesting: a number of birds, trees, and anchors represented around the site

on other monuments.

There's no evidence that these other monuments are related, but I found them

terribly interesting primarily because of the fact that Esus is represented in

Paris with a tree and birds on a pillar set up by sailors.

Food for thought, at least.

There is a second literary source for Esus, as well. Deiniol Jones pointed this one out to me recently, and I wanted to include it here: Marcellus Empiricus of Bordeaux's De medicamentis liber. The source I have on this is "A Gaulish Incantation in Marcellus of Bordeaux" by Gustav Must, Language, Vol. 36, No. 2, Part 1. (Apr.-Jun., 1960), pp. 193-197.

Included in this article is a Gaulish incantation and its explanation. Here is the incantation:

XI EXV CRICON EXV CRIGLION AISVS SCRI SV MI0 VELOR EXV GRICON EXV GRILAV.

The article goes on to transcribe and translate the incantation"

The Gaulish incantation probably reads as follows: Xi exu cricon, exu

criglion, Aisus, scri-su mio velor exu gricon, exu grilau. It means something like

this: 'Rub out of the throat, out of the gullet, Aisus, remove thou thyself my

evil out of the throat, out of the gorge.'

Here's what it says about the appearance of "Aisus" and how it relates to the more common transliteration of "Esus"

aisus represents the Gaulish divine name Aisus, recorded as Aisu-, Esu-, Esus, Aesu-, Aesus, Haesus, Hesus in inscriptions and in Latin manuscripts.16 The form in the present text is a masculine u-stem and stands in the vocative case; the vocative of u-stems was identical with the nominative. It is a widespread stem in religious terms and is attested in the languages of ancient Italy, e.g. Umbr. esono- 'divinus, sacer', esunu (neuter) 'sacrificium', Oscan Marruc. aisos (nom. pl.) 'dii', Paelig. aisis (dat. pl.) 'diis', Messap. aisa, which perhaps are loanwords from Etruscan, cf. Etr. aesar 'deus', aisuna 'divine'.17 Venetic aisu- 'god' also belongs here.l8 Further, there is an interesting correspondence of these words in Old Norse, eir, f., which occurs as the name of a goddess of medicine,19 and derives from *aisa via *aizō.

The form aisus in Marcellus is important as a record of the god's name in a

Gaulish text. As is well known, the interpretatio romana equates this god with

Mercurius and Mars, and he is mentioned as one of the three principal gods of

the Gauls (beside Teutates and Taranis). No wonder he was invoked by the

Gauls and asked to cure a troubled throat. Although Marcellus was a Christian,

many pagan elements occur in his medical instructions. The Gaulish sentence

may represent an old charm formula.

Notes

l6 - G. Dottin, La langue gauloise 60.

l7 - Vetter, Handbuch der italischen Dialekte 1.185, 38, 282, 141, (Heidelberg, 1953); P. Kretschmer, Glotta 30.88 (1943); J . Pokorny, Idg. et. Wb. s.v.2. ais-.

l8 - See M. S. Beeler, Venetic and Italic, Hommages d Max Niedermann 41 (1956).

19 - Sigfus Blondal, Islandsk-dansk ordbog s.v. (Reykjavik, 1920-22); Richard Cleasby and Gudbrand Vigfusson, An Icelandic-English dictionary s.v. (2nd ed., Oxford, 1957).

These pictures used to be difficult to come by, though my source for them was:

Mac Cana, Proinsias. Celtic Mythology. Hamlyn

Publishing, London, 1970.

Note: I recently visited the Nautes Pillar (first set of pics

below) in Paris, and took pictures of the entire thing. I created a separate page for the pictures and a discussion of the pillar as a whole: the

Nautes Pillar, or the Pillar of the Boatmen

I highly suggest reading the Mac Cana book. Good luck finding it

outside of a library.

I'll include the captions for the pictures in this book with the page

numbers. (It may go without saying, but please remember that the captions

are not primary sources.)

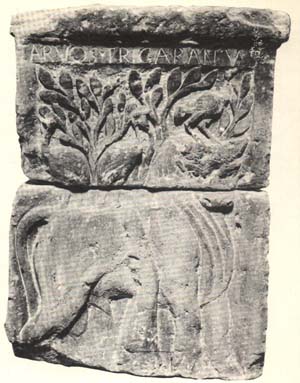

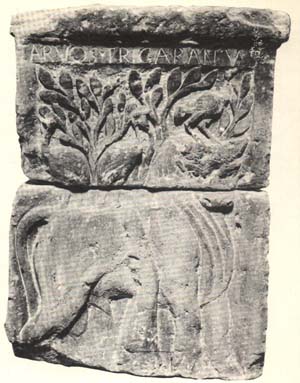

(Mac Cana, page 32, 33)

Reliefs

from a pillar dedicated to Jupiter by the 'Parisian mariners' between AD 14 and

37 and rediscovered in 1711 under the choir of the cathedral of Notre Dame in

Paris. One shows the god Esus cutting branches from a tree. In the

other there is a similar tree with a bull surmounted by three birds. It

bears the title Tarvos Trigaranus, 'The Bull with Three Cranes'.

That these two adjacent scenes belong together is confirmed by a relief from

Treves (page 35) in which a man, similarly dressed in short working tunic,

appears to be hacking the trunk of a tree in whose foliage are visible the head

of a bull and the same three birds. These three components, the sacred

tree, the divine bull and the triad of otherworld birds, are familiar features

of insular Celtic tradition, and obviously we have to do here wit some episode

from a myth. Unfortunately its precise content can only be

conjectured. Musee de Cluny, Paris. Reliefs

from a pillar dedicated to Jupiter by the 'Parisian mariners' between AD 14 and

37 and rediscovered in 1711 under the choir of the cathedral of Notre Dame in

Paris. One shows the god Esus cutting branches from a tree. In the

other there is a similar tree with a bull surmounted by three birds. It

bears the title Tarvos Trigaranus, 'The Bull with Three Cranes'.

That these two adjacent scenes belong together is confirmed by a relief from

Treves (page 35) in which a man, similarly dressed in short working tunic,

appears to be hacking the trunk of a tree in whose foliage are visible the head

of a bull and the same three birds. These three components, the sacred

tree, the divine bull and the triad of otherworld birds, are familiar features

of insular Celtic tradition, and obviously we have to do here wit some episode

from a myth. Unfortunately its precise content can only be

conjectured. Musee de Cluny, Paris.

(See further pictures, not from Mac Cana, on a separate page: the

Nautes Pillar, or the Pillar of the Boatmen)

(Mac Cana, page 35) (Mac Cana, page 35)

The

relief from Treves which corresponds to the Paris reliefs of Esus and Tarvos

Trigaramus. It shows a woodcutter attacking a tree on which repose three

birds and the head of a bull. Landes-museum, Trier.

The American Journal of Archaeology [Vol. 1, No. 4/5 (July-Oct. 1897) pp 333-387] mentions this second relief of Esus, having this to say on the subject on p. 374-375:

"From Differten comes a sandstone relief of Mercury in Gallic costume, with herald's staff and purse, an illustration of Caesar's remark that Mercury was especially honored by the Gauls. Most important is a Gallo-Roman votive monument dedicated to Mercury by the Mediomatrician Indus. On the front, on either side of an open box, stand Mercury, with winged shoes and Gallic collar, and his Gallic mate Rosmerta. On the right side, next to Mercury, is the Gallic god Esus felling a tree, above which appear a bull's head and three large birds, symbols of the god Tarvos Trigaranus, as seen on an altar at Paris. The monument is evidence of the identity of Esus and Mercury."

There is a copy of this article on JSTOR if you have access to it.

Okay, so what do other people say about Esus? Keep in mind that this is

secondary info, and not necessarily reliable. What I plan to do is put stars

next to each entry detailing what I think their worth is (take that info or

leave it, it's up to you).

There was a sampling above with Mac Cana's stuff next to the pictures. What else does he have to say about Esus?

The following sources have info about Esus, and I'll quote and cite them as

best as I can:

Ellis, Peter. The Druids. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1994. (p. 127)

Lucan adds to our knowledge of Celtic gods by stating that Esus,

Taranis and Teutates were also worshipped. He refers to 'uncouth

Esus of the barbarous altars' who has to be propitiated by human

sacrifice. Esus appears in the guise of a muscular woodcutter on

a relief dedicated to Jupiter c.AD 14-37, rediscovered in 1711 under

the choir of Notre Dame cathedral in Paris. A similar depiction was

found from the same century at Trier.

Encyclopedia of Religion (clipped from here because it's so long, so it's on it's own page).

Green, Miranda J. Dictionary of Celtic Myth and Legend. Thames & Hudson, March 1992.

(p. 93-94)

Esus The Roman poet Lucan described in a poem, the Pharsalia,

dating from the 1st c. AD, the last grate battle in the civil war between

Pompey and Caesar. In it, he alludes to the journey of Caesar's troops through

southern Gaul and their encounter with three Gaulish gods: Taranis, Teutates

and Esus (Pharsalia I, 444-6). Lucan describes this triad as cruel,

savage and demanding of human sacrifice: 'horrid Esus with his wild altars'.

In later commentaries on Lucan's poem, probably dating from the 9th c. from

Berne, Esus is mentioned as being propitiated by human sacrifice (see

SACRIFICE, HUMAN): men were stabbed, hung in trees and allowed to bleed to

death. The two commentators equate Esus with Mars and Mercury respectively,

but this may not pose as great a problem as it first appears, since the word

'Esus' is not so much a name as a title, meaning 'Lord' or 'Good Master'.

Whilst the implication of Lucan's description is that Esus was an important

and powerful Gaulish divinity, this is belied by the archaeological evidence

in which Esus may be traced to only two monuments. The more significant stone

forms part of the pillar dedicated to Jupiter by Parisian sailors in the reign

of Tiberius. The block from Paris was found with five others in 1711 on the

site of Notre-Dame. The Esus stone itself is inscribed with his name, and

beneath this is a depiction of a muscular god chopping at a branch of a willow

tree. On a juxtaposed scene is another willow, a bull and three cranes or

egrets, with the inscription 'TARVOSTRIGARANUS'. Essentially similar

iconography recurs on a 1st c. AD stone at Trier, where an unnamed woodcutter

attacks a willow in which repose three egrets and the head of a bull.

The symbolism of the two monuments, whilst not identical, is sufficiently

similar and idiosyncratic for it to be possible to identify the presence of

Esus on both. In addition to the image of the woodman, the willow, the marsh

birds and bull appear on the Paris and Trier images. The iconography is

obscure, but there is a natural association between bulls, birds, and willows:

egrets feed on parasites in cattle hide; they, like the willow, are

inhabitants of marsh or water margin, and egrets nest in willows. The

woodcutting scene is problematical in terms of interpretation. It has been

suggested that Esus prunes the tree for sacrificial purposes. It may be that

there is a cyclical imagery in the destruction and rebirth of the Tree of Life

in winter and spring: the birds may represent the soul in flight, perhaps the

soul of the tree itself; the bull could himself be a sacrificial beast.

Seasonal imagery may also be present in the symbiotic relationship enjoyed

between bull and birds, which are of mutual benefit to one another. Finally,

it should be recalled that trees are associated with Esus not simply in the

iconography buy also in the Berne commentaries which describe the fate of

Esus' sacrificial victims.

Mac Cana 1983, 29, 33; Zwicker 1934-6, 50; Dufal 1976, 26-7; 1961, 197-9; Ross

1967a, 279; Esperandier, nos. 3134, 4929; C.I.L. XIII, 3656.

Gwinn, Christopher. Post on the Yahoo! Continental Celtic Group <http://groups.yahoo.com/group/continentalceltic>

on Sat, 11 Jan 2003 20:47:33.

Esus, in my opinion, is an a-grade u-stem based on a PIE root *eis-

"passion/fury" (making the name semantically the same as Germanic

Wotanaz "Furious/Inspired God"). Alternately, I think it may be from PIE *ais-

(2) "honor/respect".

MacCulloch, John A. Celtic Mythology. Academy Chicago Pub, February 1996. (p. 157-158)

They [the Setanii and Brigantes] had a well-known god, Esus, whom d'Arbonis

identifies with Cuchulainn; whence the story (of Cuchulainn) is of Gaulish

origin, perhaps taught by the Druids; and it was ultimately carried to Ulster,

where it was received with enthusiasm.* The identification rests on certain

figured monuments, in the persons, names, or episodes of which M. d'Arbois sees

those of the saga. On one altar Esus is cutting down a tree, while on the same

altar is figured a bull on which are perched three birds, this animal being

entitled Tarvos Trigaranos -- "the bull with three cranes" (garanus), unless the

cranes are a rebus for the three horns (karenos) of divine animals. On another

altar from Treves a god is cutting down a tree, and in its branches are a bull's

head and two birds -- a possible combination of the incidents on the other

altar. M. d'Arbois regards this as illustrating the Tain. Esus, the woodsman, is

Cuchulainn; his action depicts what the hero did -- cutting down trees to bar

the way of Medb's host; "Esus" is derived from words meaning "anger," "rapid

motion," such as Cuchulainn often displayed. The bull is the Brown Bull; the

birds are the forms in which Morrigan and her sisters appeared,** though these

bird-forms were those of the crow, not the crane; the personal names Donnotaurus

is found in Gaul and is equivalent of the Donn Tarb -- the "Brown Bull."***

*D'Arbois [b], pp. 25, 65 f.,RCel xx. 89 (1899).

**D'Arbois [b], pp. 63, RCel xix. 246 (1898), xxviii. 41 (1907); cf. S Reinach,

in RCel xviii. 253 f. (1897).

***Caesar, De bello Gallico, vii. 65; d'Arbois [b], p. 49, and RCel xxvii. 324

(1906).

MacKillop, James. A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford University Press, November 2000.

Esus, Hesus. Important god of ancient *Gaul, known both from Latin commentaries and from archeological evidence; often mentioned in the company of the Gaulish gods

*Taranis and *Teutates. Although he testimony of Lucan (1st cent. AD) has been challenged as biased against the Gauls and contrived to pander to metropolitan prejudices, it cannot be ignored. He portrays an 'uncouth Esus of the barbarous altars'. Human sacrifices are suspended from trees and ritually wounded; unnamed priests read omens from the way the blood ran from the wounds. Ancient scholiasts linked Esus to both *Mercury and *Mars, the latter implying that he might be a patron of war. Depictions of Esus as a woodcutter have prompted much

imaginative speculation, but the

earlier suggestion of a link between Esus and *Cuchulainn now seems ill-founded. One temple features three symbolic representations of *egrets; he is also associated with the *crane.

Although Esus' cult was thought confined to Gaul, the discover of *Lindow Man, the body of an ancient human sacrifice found in Cheshire in 1984, implied to some commentators the propitiation of Esus in Britain. Although Esus was worshipped in many parts of Gaul, he appears to have been the eponymous god of the Esuvii of northwest Gaul, on the English Channel,

coextensive with the modern French Department of Calvados. In popular etymology his name is commemorated in the Breton town of

*Esse. See Waldemar Deonnna, 'Les Victimes d'Esus, Ogam, 10 (1958), 3-29; Paul-Marie Duval,

'Teutates, Esus, Taranis', Etudes Celtiques, 8 (1958), 41-58; Anne Ross, 'Esus et les trois

"Grues"', Etudes Celtiques, 9 (1960/1), 405-38.

de Vries, Jan. Keltische Religion. Stuttgart, Germany: W.

Kohlhammer, 1954. Trans. David Fickett-Wilbar (and much appreciated!)

p. 97: "Hesus Mars is placated thus: men are suspended in trees

even until the parts of the leg have separated."

p. 97: "They are believed to be Hesus Mercurius, if indeed he is

worshiped by sailors."

p. 98: "It can hardly be ascertained where he was worshipped. The just

mentioned sources point, at any rate, to a not inconsiderably widespread

distribution. That his cult flourished mainly in the area around Paris is at

least likely.

Three clues offer themselves to the meaning of this deity: 1. his name 2. the

kind of sacrifice offered to him 3. the ritual act on the altars from Paris

and Trier. We will examine them in turn.

The word "Esus" is not unknown in Gaulish. We find it in the

personal names Esunertus, Esumagos, Eusmopas, Esugenus (n. 4. This name is

found in Irish Eogan, in Welsh Ewein, Owain); even simply as Hesus. Perhaps

also the name of the Esuvii tribe belongs to it. The explanation of this word

can be broken up further, however. Dom Martin seeks a connection with the

Breton word (h)euzuz, meaning "terrible." Others have thought it

from Italic aisus, esus, "God," and the Etruscan Erus or also from

the Latin herus, "Lord, Master." On the other hand, Vendryes

explains the name from esu, "good" (cf. Gk. eus and also archaic

Indic asura); but we hardly get the impression of a good god from the Berne

scholia. Others would like to derive it from the Indo-European root *is,

"to desire;" then arguing the sense: the one who fulfills men's

desires. Perhaps better might be the derivation from the root *eis, which

means "energy, passion." These are, however, only possibilities,

which prove one more time that one can't come far with etymology.

That the scholia refer to horrible sacrifices also give us few clues to the

significance of the god. Already the expression membra digesserit can not be

understood. Must one understand by it, "to tear up, to cup up?" Or

do we rather have to deal here with a disposition of the limbs after the blood

has flowed out? It is important that the sacrifice would be hung from a tree,

because a tree likewise stands out as full of meaning in the pictured

representations. The objection that we hear only seldom of hanging rituals

among the Celts and that the chopping off of lime is completely unknown [ed. note: begin p. 99]

says little. What do we know about the bases of Celtic sacrifice? What the

classical authors have told us of it is in any case terrible enough. If we

consider the reports of these sacrificial practices reliable, Esus must seem

to us to be a god of little friendliness.

Finally, the portraits from both altars. To what purpose does the god strike a

tree? It seems to me completely erroneous to think of a simple forester god,

and to connect Esus with clearing-work, or to see in him at all a manual

laborer who provided the nautae of Paris with the necessary workforce for

their ships. Likewise it is incorrect that the cutting down of trees would be

regarded as a death, and then further to remind us of Maypole rituals. It

seems even more to me that Esus in the picture is cutting the limbs of a tree;

if one imagines that sacrifices for him were only just hung on the tree, once

comes perhaps to the conclusion that god would have been shown here by the

injury of a tree for the hanging-sacrifice.

We must admit, with W. Deonna, that the meaning of the myth is for us

incomprehensible; perhaps the picture only refers to a single piece of the

ritual. At any rate, I would like to assert that there can be not talk of a

"rural" god of clearing-work. The relief of the blocks from Paris

represents him in the same rank as Jupiter and Volcanus. The Berne scholiasts

compare him with the great Roman god; it remains only questionable whether he

is Mercury or Mars or perhaps neither of them. The Esus-complex has also been

compared with Hercules, and it has been pointed out in that regard that

figures of bas-reliefs with the name Smert… are themselves found; one could

consequently think of a Gaulish Herakles or Donar, thus of a god of physical

strength.

But that will not explain the hanging-sacrifice. When one accordingly takes

this into consideration, the comparison with Mercury gains special meaning. If

the German Mercury is simply Woden-Odhin, this go stands in undoubted

connection with an act of sacrifice by means of hanging. It can likewise be

said of both gods that they are also gods who protect travel: Odhin is called:

[ed. note: obscured], thus "god of cargo;" he gives mariners

good winds. The Paris altar was erected by nautae. On the other hand, one is

reminded how cautious one must be with one's interpretation. Great gods are

always ambivalent; their power extends into many areas of life. Odhin is not

only a god of force, but of tricks and intrigues, of crafts and skillfulness.

Exactly for these reasons could the mariners have worshipped him. The god to

whom the hanging-sacrifice was offered was also, however, a cruel god. In that

vein one could point to the name "Esus," if one accepts O'Rahilly's

etymology; but also the interpretation of Vendryes deserves consideration, if

one thinks that the name "the good god" is perhaps to be considered

as only a euphemism.

All in all: the account of the hanging-sacrifice and the picture on the Paris

altar sets out as the nearest course of assumption that Esus was a name for

the head god of the Gauls and perhaps most likely to be compared to Mercury

and the northern Germanic Odhin.

From http://www.britannia.com/celtic/gods/esus.html

(While a travel site, it has some things to say that might be useful):

Esos

Celtic God of the Willow

Though there is no direct evidence for the worship of Esos - the ‘Good Master’ -

in Britain, and little elsewhere, he is mentioned by the Roman poet, Lucan, as a

powerful Celtic god encountered by Caesar’s troops in Southern Gaul. Equated with

Mars, he was apparently savage, cruel and "Horrid Esus with his wild altars" demanded

human sacrifices. Later commentators indicate that the male victims were stabbed,

hung in trees and allowed to bleed to death. The implication is that Esos was widely

reverred, but archaeological evidence is scant.

He is best attested on a large decorated pillar bearing his name, but dedicated to

Jupiter. It was discovered below the Notre Dame in Paris in 1711 and depicts a muscular

man chopping away at a willow tree. A juxtaposed scene shows a bull with three cranes

or egrets on its back, named Tarvostrigaranus - the 'Bull with Three Cranes'. Similar

iconography appears on a stone from Trier.

The symbolism is almost impossible to interpret and may relate to some long lost

mythology. The Willow and the Cranes are associated with the water's edge, so perhaps

Esos was a marshland god. The tree is presumably that in which his victims were

sacrificed, by why he prunes it is uncertain. Possibly it shows the destruction and

rebirth of the Tree of Life in Winter and Spring. The birds may represent spirits

during the former process. They are natural and matually beneficial companions for

the Bull, which enhances the fertility symbolism of the tree. Magical groups of three

birds appear in Welsh mythology and, to the Irish, cranes may reprsent women. In this

context, the Tarvostrigaranus may just possibly be represnted by a small bronze

triple-horned bull figurine found at the Roman Temple within the hillfort of Maiden's

Castle (Dorset). It shows three female humoid figures perched on its back.

Mary Jones, an excellent Celtic scholar, has entries on both Esus

and Tarvos Trigaranus, as well as the

Nautes Pillar. I

would encourage you to visit her site, and so won't copy/paste the contents

here.

What can we infer from these sources?

Esus is represented with certainty only three times. You see those three

above, two from the Nautes Pillar and one from Trier. In the first representation, we see Esus represented as a bearded man

wearing a loose tunic. His clothes are primarily dictated, I think, by the

relief itself, as this representation, dated to 14 AD, is a Romanized representation.

Interestingly, the term applied to a man wearing only a tunic was nudus

in Latin, and thus we have a god who appears to do the work of a common man

(i.e. a woodcutter) being represented on the level of that common man.

It does seem that he is cutting down a willow tree with his hand-axe,

representing a possible connection with the breaking of barriers and the areas

between worlds (the willow tree stands at the place between the worlds of land

and water). He may also be trimming the tree with a bill-hook, possibly an

indication of the need to re-work the world tree or to trim the parts of it that

are dangerous or diseased.

The relation between the Esus panel and the Tarvos Trigaranus panel seems

obvious, given the Trier relief. There is question about how they are related,

obviously, in particular about whether they illustrate the same scene, or two

different scenes. Do we take the four sides of the pillar section as one story?

Could the myth be related along the entirety of the pillar, with each character

playing a specific part in this mythic drama?

The representations may also be of a hero, not a god at all. If this is the

case, then we may have been looking at it from a direction that prevents our

understanding. We can say that a number of the figures on the Nautes Pillar

are not deities, and so this may be another non-deity.

The Three Cranes:

A set of three cranes appears a few times in some Celtic lore, but the one

that comes to mind most quickly is the story of Athirne the Unsociable. Whether

this is connected to Esus or not is debatable at best, as the names don't seem

to match up, nor does it well reflect what we see in the relief:

Athirne the Unsociable

From http://www.geocities.com/paris/arc/6084/ath-un.htm

Translated by Patrick Brown

Athirne the Importunate, son of Ferchertne: it's he who was the most inhospitable man who ever lived in Ireland. He went to Mider of Brí Léith and brought the three cranes of exclusion and inhospitality away from him to his own house, for the sake of stinginess and inhospitality, so none of them men of Ireland would visit his house expecting celebration or entertainment.

"You're not coming in," said the first crane. "Get out of here," said its companion. "Keep walking," said the third crane.

From that day on, none of the men of Ireland who saw them would go to his door.

He would never eat his fill where anyone could see him. So he went with a cooked pig and a wineskin of mead to eat his fill by himself. He was settling himself down in front of the pig and the wineskin when he saw a man coming towards him.

"You were going to eat that by yourself," said the man, striking the pig and the bottle from him.

"What is your name?" said Athirne.

"It's not well known," said the man. "Sethor Ethor Othor Sele Dele Dreng Gerce mac Gerce Ger Gér Dír Dír, that's my name."

Athirne couldn't compose a satire on that, so he didn't get the pig back. It may be that the man was sent by God to take the pig, for Athirne stopped being unsociable from then on.

It is possible that there is a connection between the Athirne and Esus myths,

but I'm not sure that there is. The change from a pig to a bull is quite a large

change, really, and while the cranes seem to be

So now you want to know how I see him, hmm?

For now, you'll have to wait. I'll update soon. First I want to get the

scholar's works out of the way.

Back to the Patrons

Index.

Back to the Dedicant's

Index.

Content © 2003-2007, Michael J Dangler

Updated on 12/11/2007. Site Credits / Email

Me!

Basic site design from ADF.org

(Yes, I stole it!)

|